Lee Hachadoorian

Spring 2023

Based on materials created by Xiaojiang Li, PhD, Department of Geography and Urban Studies, Temple University, http://www.urbanspatial.info/. Forked from Prof. Li's Spring 2022 course repo at https://github.com/xiaojianggis/big-spatial-data/.

UNDER CONSTRUCTION: Some of the materials are being altered. Numbering generally corresponds to course weeks. Associated assignments appear in Canvas. See my notes regarding the state of each notebook, as well as notes below regarding preparing your environment, obtaining data, and what changes I am making and why.

Most of the materials in this repo are Jupyter Notebooks. You can create a Python environment in any way you wish, but instructions are provided below for creating a conda environment using the YAML environment file included in this repo.

For the most part this course assumes you are working in an Anaconda Python environment and familiar with Jupyter notebooks. If you need to install Anaconda, you can follow the instructions in #1. I have a preference for Miniconda (smaller default installation size, and you can add anything from Anaconda that you are missing later). I will introduce Jupyter notebooks in class, but #2 provides a short guide. Most of the students taking this course will already be familiar with basic Python, including importing and plotting spatial data. #3 provides a brief refresher.

These notebooks are short and will be combined into one longer notebook.

The exercise Using Fiona to manipulate shapefiles and do spatial analysis has the following sections:

- Read Shapefile using Fiona

- Using Fiona and Shapely to overlay shapefiles

Currently nonworking. Need to obtain certificate file for NAIP download.

- Download NAIP images automatically

- Using Rasterio to manipulate geo-reference raster data

- Mosaic, mask, clip

- Calculate NDVI

- Overlay vector data on raster (zonal statistics)]

- Install Postgres/PostGIS

- SQL Basics

- Spatial Analyses through SQL queries

The exercise Database operations in Python has the following sections:

- Access Postgres/PostGIS database using Python

- Read shapefile and save features into database tables using Python

- Save query results into shapefiles using Python

Visualizing half-million building blocks online

This exercise covers the following steps:

- Convert shapefile to geojson and mbtile

- Using Mapbox studio to visualize building blocks

- Using GitHub to host your web map

TL;DR Download geospatial-environment.yml (or just clone this repo). Open the Anaconda Prompt. Navigate to the directory with the environment file and run the following conda command:

conda env create -f geospatial-environment.yml

This will create a conda environment named geospatial with almost all of the packages you will need for the entire semester.

You can create your Python environment in whatever way you are comfortable. I prefer using Anaconda, and that is what I will show in this class. If you prefer to work with Python environments using pip or some other way, this is the list of packages that you need:

- geopandas

- rasterio

- descartes

- jupyter

- matplotlib

- sqlalchemy

- psycopg2

- boto3

- smart_open

- scikit-learn-intelex

- progressbar2

- tqdm

- pysolar

If you use pip, all of these packages are available in PyPI.

If you use Anaconda, I have set python=3.8 to avoid unsatisfiable package conflicts. All of these packages are available in the default conda channel except pysolar. The conda environment file has the line - conda-forge::pysolar commented out. You can experiment with uncommenting it, but I have found that attempting to install it at environment creation takes an inordinately long time and often fails. Without it, environment creation runs pretty quickly (2-3 minutes). You can install pysolar afterward, and this works consistently (and quickly), even if Anaconda can't figure out how to do it in one go. Resorting to pip for pysolar or any other package seems unnecessary, so long as you are working with Python 3.8. You can install pysolar by activating the new geospatial environment and calling conda install:

conda install -c conda-forge pysolar

Additionally, I have included Spyder (my preferred IDE) and PyQtWebEngine (necessary for Spyder to run, but for some reason not a dependency). If you will stick to the Jupyter Notebooks or prefer another IDE, you can remove or comment out the following lines in the environment file before creating the environment:

- spyder

- pyqtwebengine

How you manage your Python environment is up to you. The advantage of Anaconda is that it is not just a repository but a full package management system that takes care of complex dependencies for you. This is important for geospatial data. Prior to Anaconda, it could be quite dodgy to install gdal for Python, which depends on the GDAL C++ library. The GeoPandas project recommends installing GeoPandas with Anaconda, and specifically warns of the pitfalls of the pitfalls of installing with pip.

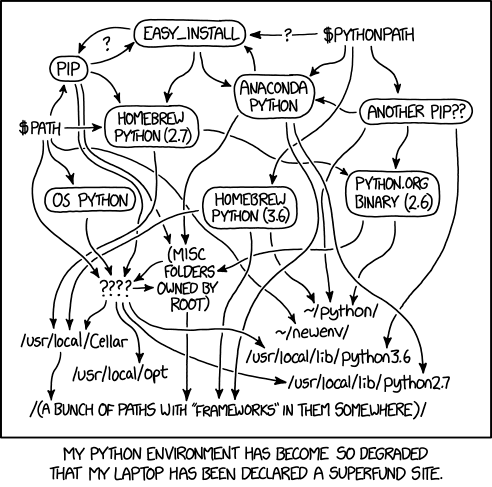

Since all of the packages needed in these lab exercises are available in conda channels (almost all in the default channel), I've removed !pip install some_package statements from several of the notebooks that I inherited. I've done this for two reasons. For one, notebooks are for analysis, and I don't think package installation should be included in a notebook (sometimes somewhere in the middle of the analysis). Your environment should already be set up, or instructions to set it up should be at the top, or in an addendum. But apart from the issue of when packages should be installed, you also should avoid mixing pip and conda as much as possible. Again, Anaconda is a package management system. Pip works completely differently, and will impolitely shove its packages into your environment, probably linked against libraries not in the conda environment, and possibly creating the kinds of conflicts that conda checks for and avoids. Sometimes, unsatisfiable package conflicts may force you use pip to install a package that conda refuses to, but you definitely shouldn't do this as a first resort. Mixing different Python installation methods can lead to this:

If you find a wayward pip install in these notebooks, please bring it to my attention.

You can download individual notebooks and data files as needed. However, the easiest way to acquire the notebooks and data is to clone this repository:

https://github.com/leehach/big-geospatial-data.git

If you don't have Git installed, you can instead download the repo as a ZIP. Of course, if there are changes, you will have to redownload changed files or the entire repo, whereas if you clone the repo you can update the files with git pull.

Some notebooks require downloading data that is not stored in this repo (usually large files or data available via API).

The repo contains an untracked output directory. When you create this repo, you should create output as a subdirectory of your main working directory. The notebooks will direct all created data to this repo. In some instances, large file downloads may also be expected to be read from output. This somewhat violates the nomenclature, but allows us to maintain one untracked directory for files that we don't want to accidentally end up in the remote.

I will loosely follow PEP 8 – Style Guide for Python Code. Without reviewing it exhaustively, the main thing to keep in mind is that function and variable names should be lower_case_with_underscores. Since this convention is also common for table and column names in PostGIS and some other DBMSes, we will also use lower_case_with_underscores for (Geo)Pandas data frame column names. (But keep in mind that many imported data sets will not follow this conventions, and we may or may not spend time "fixing" them before we work with them.)

Much of the vector data I inherited for this course was in the ubiquitous shapefile format. There's a long list of reasons why you should stop using shapefiles. I've converted all of the shapefiles to GeoPackages (using convert_shp_to_gpkg.py), and adjusted the scripts so that all vector output is to GeoPackages instead of shapefiles. Please let me know if I've missed something.

I prefer double quotes for "strings". The reason for this is that I often have to write strings with SQL statements, and SQL requires the use of single quotes as a string delimeter. "SELECT * FROM table1 WHERE column1 LIKE 'something%';" looks much nicer than 'SELECT * FROM table1 WHERE column1 LIKE \'something%\';'.

For string formatting, I strongly prefer f-strings (available in Python 3.6+). See Python 3's f-Strings: An Improved String Formatting Syntax (Guide) if you aren't familiar with f-strings. I'm still revising the notebooks to use f-strings consistently.

There are some recommended conventions which I won't be following. It's a best practice to put all imports at the top of a module. Since we're going to be using these notebooks primarily for instructional purposes, there is a benefit to showing the import statement just before using the object that you've imported, with explanatory text explaining what you're doing. Having all the imports at the top may work for software design, but starting off a pedagogical notebook with a long list of imports is not great.